from

'practice makes perfect:

theorising method in visual research'

swansea metropolitan university

6 September 2012

making sense:

the place of language

in science and art

Although I am primarily a visual artist working in paint, I decided it was time to give words a go after attending a panel discussion recently held by University of the Arts London called “What is a Good Drawing”. In order to illuminate this question, each panelist was asked to turn that around and suggest a bad drawing. The first one up chose the partition map of Palestine from 1947 as his example and said that it was not only technically a bad drawing, but even worse; it was bad historically, geographically and culturally. In response, one of the other panelists, an artist, objected to this choice and said that the map wasn't art at all, but politics. He then suggested that “when art meets politics it’s a car crash. It shouldn't happen.”

I’m always appalled when I hear someone say this because it is so profoundly wrong and so rarely challenged. I’m even more appalled when it comes from another artist. This sums up a disturbing, and all too common view of the role of art in contemporary life. While the intent may actually be artistic arrogance—that somehow art’s above all this and shouldn't get its hands dirty—what I hear is the suggestion that art’s irrelevant and has nothing more to offer than anecdotal illustration and frivolous decoration. More importantly, the statement also implies, again wrongly, that the language of the artist is categorically different from other languages and, unlike these important ones used by the political mapmaker or theorist, has nothing to say when things get all serious out here in the real world.

But how did the arts become so marginalized? Why do so many people believe that artists shouldn't play a part in exploring issues or resolving conflict and what can be done about it?

The answers, I think, can be found in the way we use language and in particular, how the development of modern thought has been so profoundly influenced by the Cartesian method of reductive reasoning. Exploring this methodology and how it’s used will not only show us how the arts have been excluded but it will also expose its limitations and show us that the voice of the artist now needs to be heard if the general discourse is to mature.

FIRST, WE MAKE ART

Before we wrote, we spoke; before we spoke, we drew; before we drew, we gestured. Each of these acts creates a symbol that gives some kind of form to our experience. Each one of them refers to an idea that has deeper meaning for us. We embed these symbols within other symbols and then embed those within even more. Each joins with the others to create complex ideas that allow us to make sense of sensation and paint an image in our heads of life in the world outside.

Essentially, this making of sense is the making of art. Each of our brains is the artist; it gathers information from the surrounding chaos and reassembles it in ways we can understand and share. Together, we’re able to create an intricately detailed picture of the world that extends far beyond the one each of us alone can see with our eyes or touch with our hands.

So, first, we make. And then, we make sense. It’s not for nothing that the theorist Ellen Dissanayake suggests we call ourselves not Homo sapiens but Homo artifex: the Making, or Artistic, Man.

THEN, WE MAKE LANGUAGE

Making these marks and sharing what we know inevitably leads to their formalization in language—and by language I mean any documentation that facilitates the transfer of information. We speak, write, dance and draw to give formal shape to what’s inside our heads. Our goal (at least from an evolutionary viewpoint) is to communicate as much of this information as possible to as many people as we can. And the most effective languages are those that travel across time and place with a minimal loss of meaning.

By this definition, our most successful language to date is mathematics. Its phenomenal ability to communicate meaning and create virtual worlds comes from its very simplicity. Each symbol references a very specific and (relatively) fixed idea; once its vocabulary is learned, it can be transmitted from person to person and from place to place without loss of information or coherence; the meaning of E =mc² remains the same wherever it’s written.

AND FINALLY, WE MAKE SCIENCE

Mathematics then became an even more powerful language with the introduction of Descartes’ Scientific Method of reductive reasoning. This method tells us that we only know what’s really important after we've removed all extraneous information from the frame of reference and reduced all argument to its first principles. By reducing everything to constituent parts, eliminating context and applying simple rules of logic, the Cartesian method evolved into a way of thinking that has become so prevalent it now provides the framework for all public discourse.

However, when we follow Cartesian rules, discard context and return to first principles it turns out we've also discarded art. That context is where the art lives. Eliminating it from the framework eliminates the language of art and silences the voice of the artist.

But as the general discourse itself has evolved over the last 360 years, it’s become apparent that this is loss of context is a profound flaw. When we follow the method to its logical conclusion and reduce a universe (or argument) to its elements and then situate it within a context-free environment, we discover we know next to nothing about how it all works. And even less about what it means to us.

Knocking something back to its basic building blocks only gives us a catalogue of parts; it doesn't provide us with a manual for making them run. And understanding how something runs is critical to understanding what it means. For example, knowing that the sun heats the earth is not nearly as important as understanding what happens to our environment when it does. In this case, our survival may depend upon understanding an elaborate collection of networked systems all influencing—and being influenced by—each other.

Without understanding the context of our experience the knowledge we have is nearly pointless. As Sir Martin Rees said in his BBC Reith Lectures of 2010, “Reductionism is true in a sense, but rarely in a useful sense”. It’s when the missing context is added back that what we know begins to make a useful sense.

ART IS BACK IN THE GAME

Reintroducing context, the home of art, means the art practitioner now has the opportunity to actively contribute as more than just a passive commentator. New discourse requires new thinking and new thinking requires new language. The inherent skills of the artist are well suited to these more holistic discussions. While reductive reasoning has led the traditional thinker into narrow streets and meaningless dead-ends, the artist has always roamed far and wide, exploring other fields and developing new ways to articulate them as she goes. Working outside the strict parameters of the Cartesian method allows the artist more of an opportunity to truly blend disciplines and openly entertain the improbable. And it’s when the improbable is entertained that inspiration occurs.

These inspirational moments, common to the artist, are integral to the advancement of knowledge. And in the right circumstances they have the potential to completely change the direction of human thought. Albert Einstein was famously inspired when he tried to chase light on his bicycle, Descartes defined coordinate geometry while watching a common house fly from the comfort of his morning bed and, of course, Newton had his apple. History shows that these moments don’t necessarily take place at the heart of a scientific discipline but near the edge of it (on a bed, bicycle or tree) where intellect meets emotion and impossibility gives rise to originality.

While some moments of inspiration are certainly astounding, each starts its life like every other. Einstein first had his great idea and then, like the rest of us, sat down and described it. Communicating what he knew meant shaping that idea so others could understand it and mathematics was only one of many languages he could have used to do that. Like a poem or a painting, maths simply drew a shape around his idea to contain its meaning and make it visible to others.

The artist, however, has a more difficult task. Where the scientist uses an existing vocabulary, the artist must build a brand new one. If he wants to be part of a wider critical discussion he first must draw shapes to formalise his thoughts and make them relevant. Unlike maths, however, the artistic language can be more nuanced and multi-layered; the artist can mine a richer, more complex set of symbols to make meaning.

The difficulty, of course, lies in the contextual knowledge required to understand what the artist means. To read a language you must know the words. The scientist achieves this by building upon a collection of symbols that have grown over time. In the same way, the artist needs to develop a vernacular that becomes more consistent and coherent with use. Each mark of the brush and every colour on the palette; each sound made and every image used; even the canvas or paper--all elements, no matter how small or inconsequential, are a part of the alphabet. They each communicate something and build upon the others to make works of greater meaning. And then each of these works build upon the one before. In this way the artist creates a powerful language that breaks away from its origins and lives in the wider world.

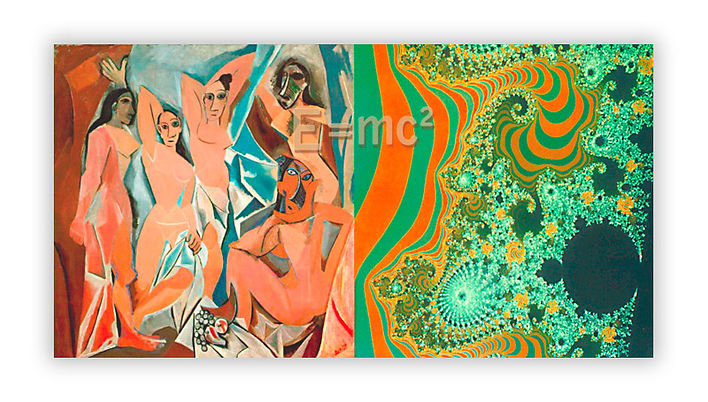

Occasionally there are those who are so successful at this their languages change history: Picasso painted Cubism and Einstein wrote of Relativity. It’s no coincidence that these works developed concurrently; Einstein and Picasso both lived in a world headed towards war and they explored it from perspectives that were surprisingly similar. Picasso and the Cubists manipulated paint and shape to reorder the world so different views could be seen all at once. Einstein used his maths to do the same. Each of them developed a language unique to themselves that was more powerful and effective than what came before.

And they didn't work in isolation: Einstein was aware of Picasso and Picasso of Einstein. While neither suggested (nor admitted) that the other directly influenced their original work, there is little doubt that the language of each has affected the other. Understanding the notions of time implied by Einstein’s relativity becomes easier after seeing the multi-perspectives of Picasso’s paintings.

AND THEN IT ALL WENT WRONG

Unfortunately, though, our culture appears to have lost sight of just how influential the arts can be when they engage with a world outside their own. We no longer have our Guernicas.

Art is now mostly found in hallowed halls or millionaires mansions and the art practice itself seems to be primarily a way of responding to the shallowest layers of contemporary life or as a means for self-reflection.

Since it’s tacitly accepted that the language of art is no match for the elegance and simplicity of logical reasoning, the contemporary artist has been let off the intellectual hook. And if the artist’s message is nothing more than knee-jerk reaction unchecked by intellectual precision or a sensible vocabulary it’s no wonder it’s a car crash when his art meets the world.

ART SAVES THE DAY

Interestingly, it’s in the realm of science where we begin to see a re-synthesis of the arts and intellect. New theories in chaos and complexity demand to be written in a context-rich, visual language. These are so complicated and elaborate that pure, un-aided thought cannot illuminate them. The only way to grasp them intellectually is to experience them visually.

Mandelbrot’s Fractal Geometry is the most familiar example of them. Working as a mathematician in the 1950s, Mandelbrot began studying the movement of cotton futures on the stock market. Digging through years and years of historical data he began to glimpse complex patterns hidden deep within the numbers. Suspecting what these patterns might mean, he developed the Mandelbrot Conjectures--three theories that describe the way networks behave and how reality is built. But his big idea isn't found in the simple equations at the base of those theories, it lives (like art) in the environment created by their continual iteration in a feedback loop. Once started these equations bootstrap up from simplicity to complexity and result in a brand new way to represent the world.

But Mandelbrot’s moment of clarity couldn't be described in mathematics alone. He required a new language to make it possible for others to understand what he saw—something that shared the Cubism of Picasso with the mathematics of Einstein. As he said himself, “The notion that these conjectures might have been reached by pure thought — with no picture — is simply inconceivable”.

Mandelbrot’s work even changed the very definition of science itself. Following the acceptance of his theories, the French Council for Scientific Research released the following statement:

Mathematics operates in two complementary ways. In the 'visual' one the meaning of a theorem is perceived instantly on a geometric figure. The 'written' one leans on language, on algebra; it operates in time.

For artists, the word ‘complementary’ in this statement is revolutionary. It boldly states that thinking visually is an equally valid approach to intellectual thought and a necessary part of the evolving discourse. It even subtly infers a need for new language to qualify it.

IN CLOSING

Exploring our world is a pointless exercise if we don’t apply meaning to what we find. That meaning is found in the rich environment that surrounds what we know and art is at its very core. Re-evaluating the Cartesian paradigm shows us how to re-introduce that context to the discourse and return a voice to the artist.

Learning why the language of mathematics has been so successful is the artist’s first step towards understanding what language is and recognising its importance in the artistic endeavour. Understanding how that language is used gives the artist a model for developing his or her own unique system of symbolic meaning. And then, using that system with consistency provides a structural framework from which intellectual thought may be more deeply developed and shared with others.

Like Picasso, Mandelbrot or Einstein, cultivating a fluency in a rigorous language opens the door to interesting and original thought. It provides the artist with a way to re-engage in a constructive dialogue and recognize that a map of Palestine is more than just ‘politics’ and a painting is more than ‘just’ art. Both are a part of a language that is absolutely vital to the discourse.